From time to time I share notes about the books I’ve been reading, or have revisited recently after many years.

These posts are meant to help me remember what I’ve learned, and to point out titles I think are worth consulting. They’re neither formal book reviews nor comprehensive book summaries, but simply my notes from reading these titles.

For previous postings, see my Book Notes category.

The Other One Percent: Indians in America

By Sanjoy Chakravorty, Devesh Kapur, Nirvikar Singh

Published in 2017

Oxford University Press

ISBN–10: 0190648740

Amazon link

Brief Summary

An illuminating look at how Indians in America – a tiny percentage of the overall population – have come to enjoy such outsized success.

My Notes

The jacket copy sums up nicely the miracle that is Indian immigration to America:

One of the most remarkable stories of immigration in the last half century is that of Indians to the United States. People of Indian origin make up a little over one percent of the American population now, up from barely half a percent at the turn of the millennium. Not only has its recent growth been extraordinary, but this population from a developing nation with low human capital is now the most-educated and highest-income group in the world’s most advanced nation.

You read that passage, and the title of the book, right: There are only about 3 million people of Indian origin in the U.S.

That’s an astoundingly low number when you consider their prominence in tech, medicine, finance and more. As a group, they have much higher levels of education and income than other citizens.

How’d that happen?

The short story: A U.S. immigration act in 1917 virtually terminated immigration from Asia. But changes to the law in 1965 opened things up, and thus began an influx of Indians.

But not just any Indians.

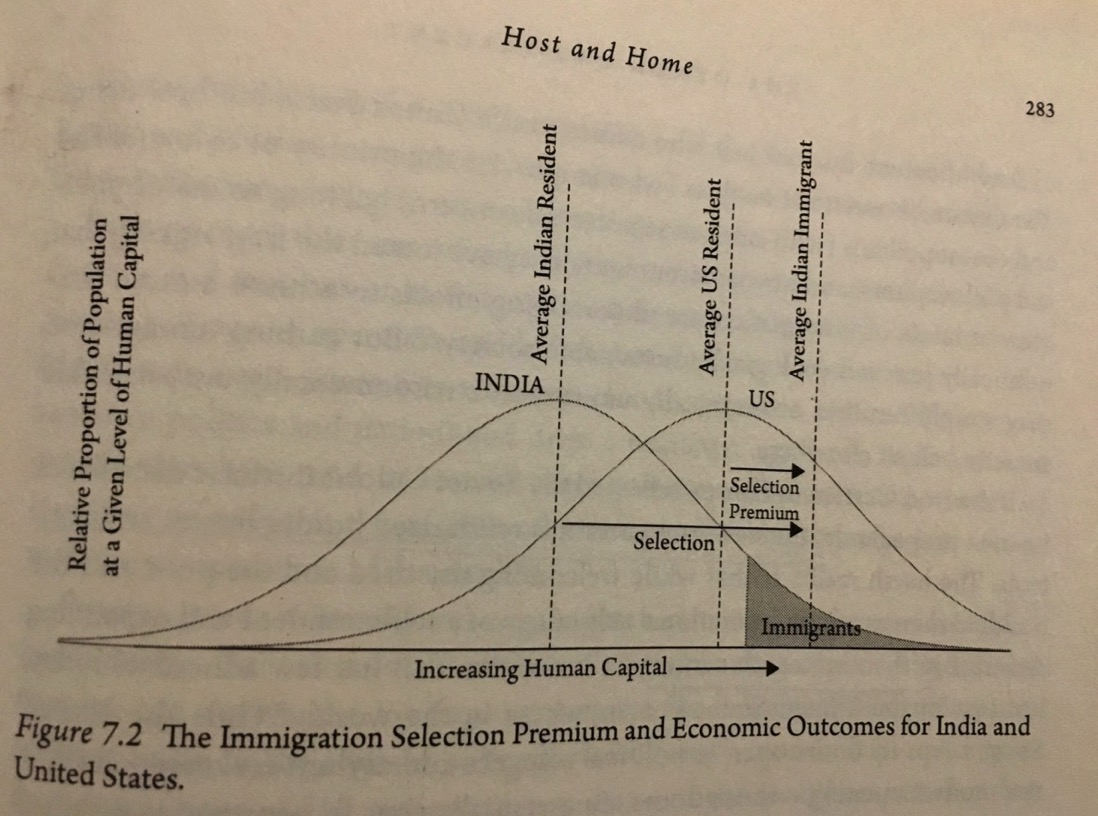

The authors – academics at Temple University (Chakravorty), the University of Pennsylvania (Kapur) and the University of California, Santa Cruz (Singh) – argue that Indian immigrants were “triple selected”:

- They came from dominant castes and had access to higher education

- They were selected to take exams in tech fields

- They benefitted from U.S. immigration law, which favored immigrants with tech skills

The book is absolutely brimming with data, and makes for a fantastic resource. (One reason I read substantive books in paper rather than on a Kindle is so I can underline passages, take photos for blog posts like this one, and then put them back on my shelf for future use!)

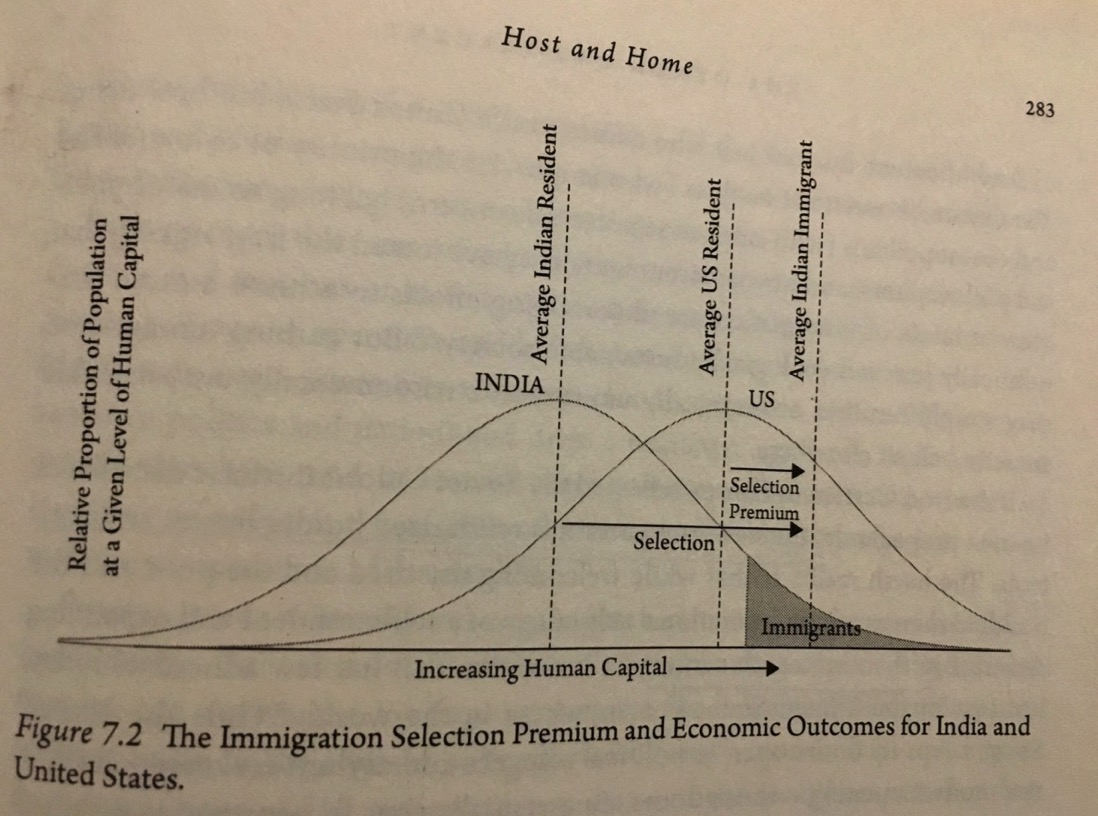

“The Other One Percent” contains some excellent graphs and charts, like this one, illustrating just how exceptional this population is:

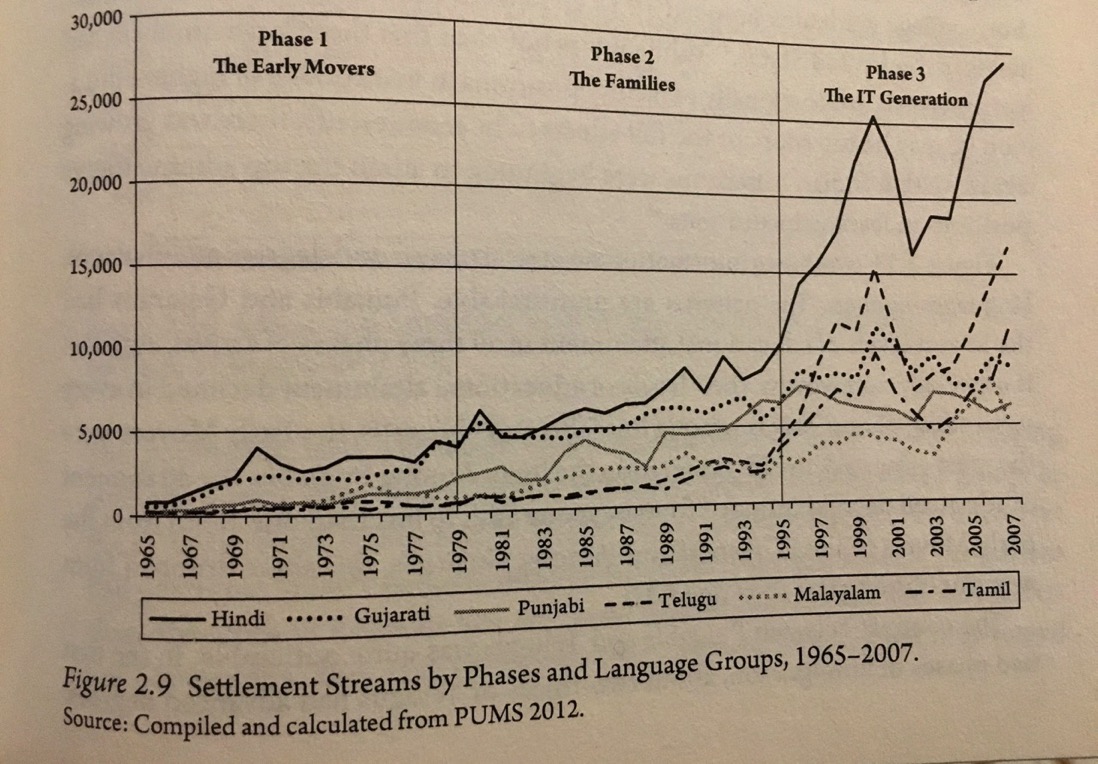

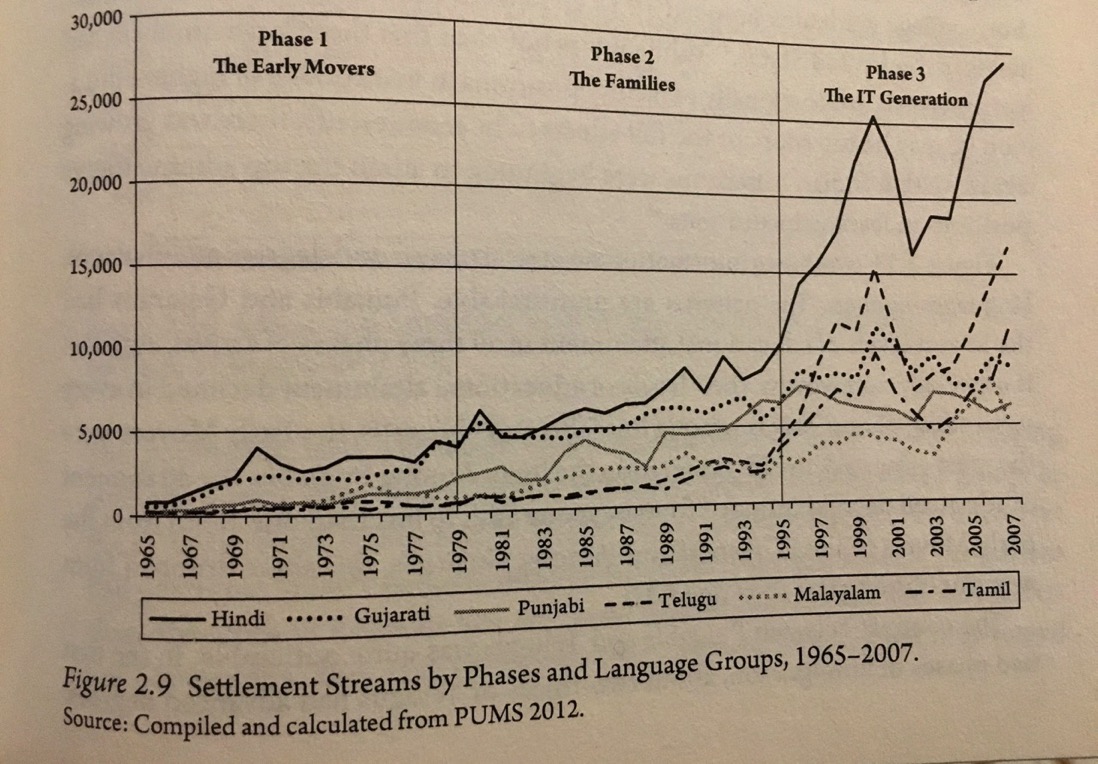

There were three phases of Indians coming to America:

- The early movers, in the 1960s and 1970s

- The families (1980s through early 1990s)

- The IT generation (after the early 1990s)

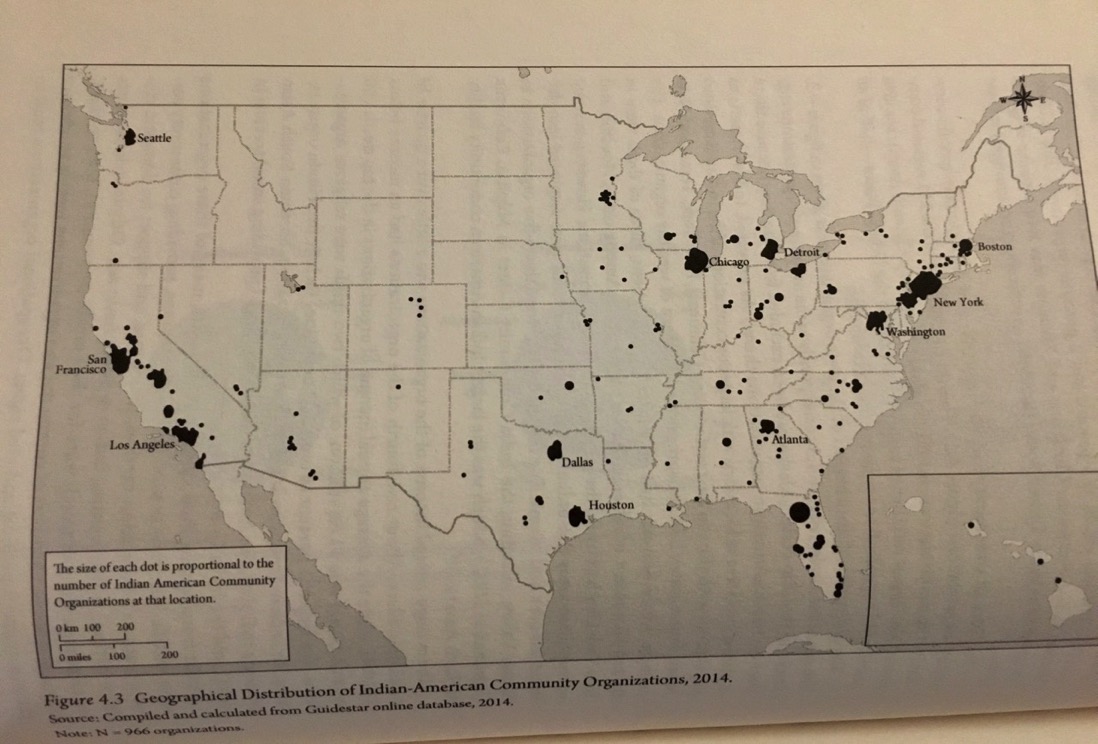

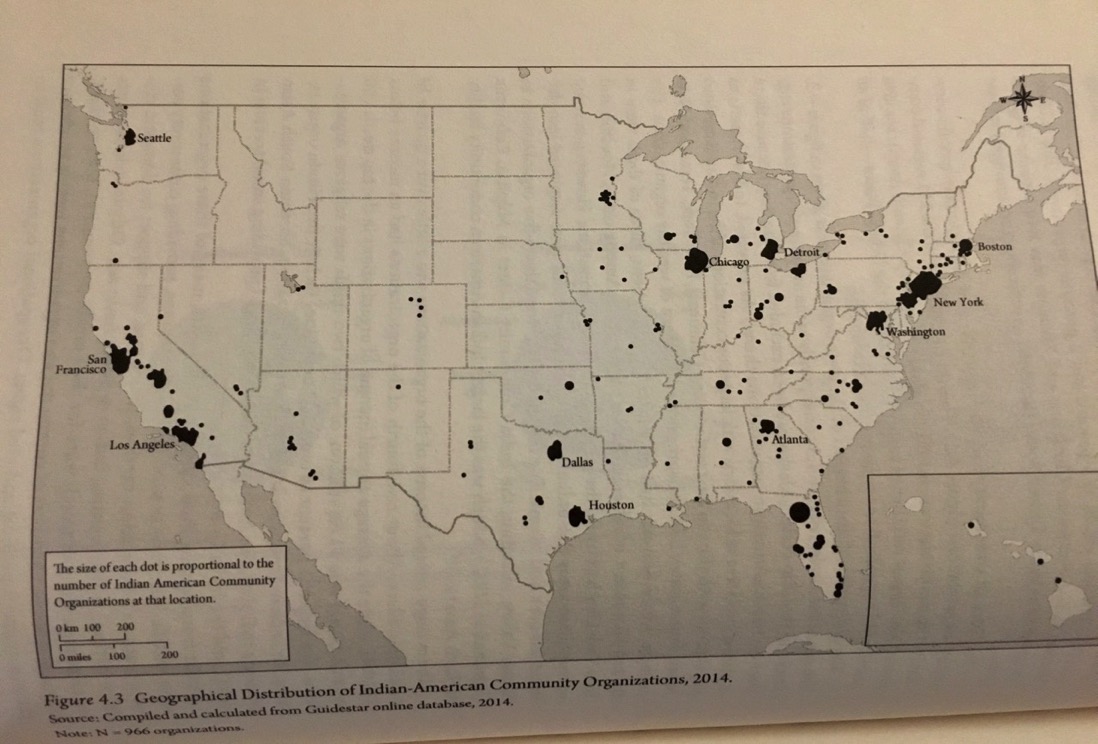

Here’s a map of where Indian-Americans tend to be clustered in the U.S., based on community organizations:

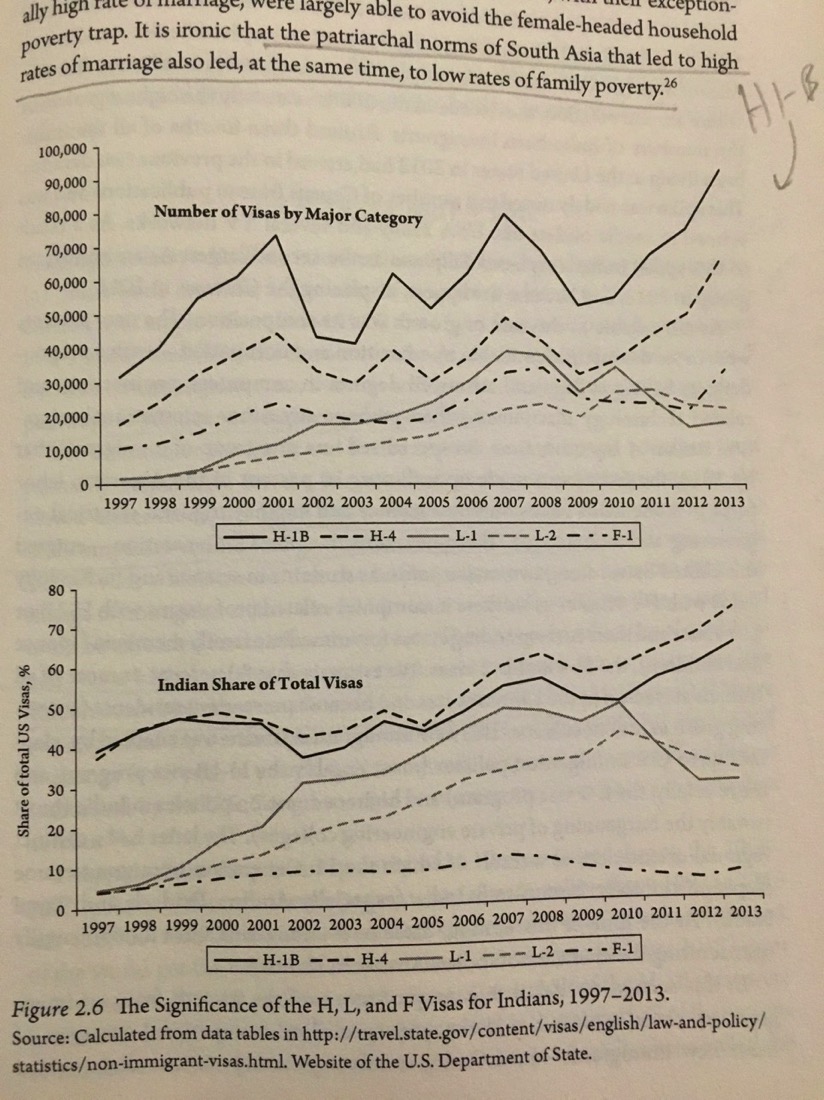

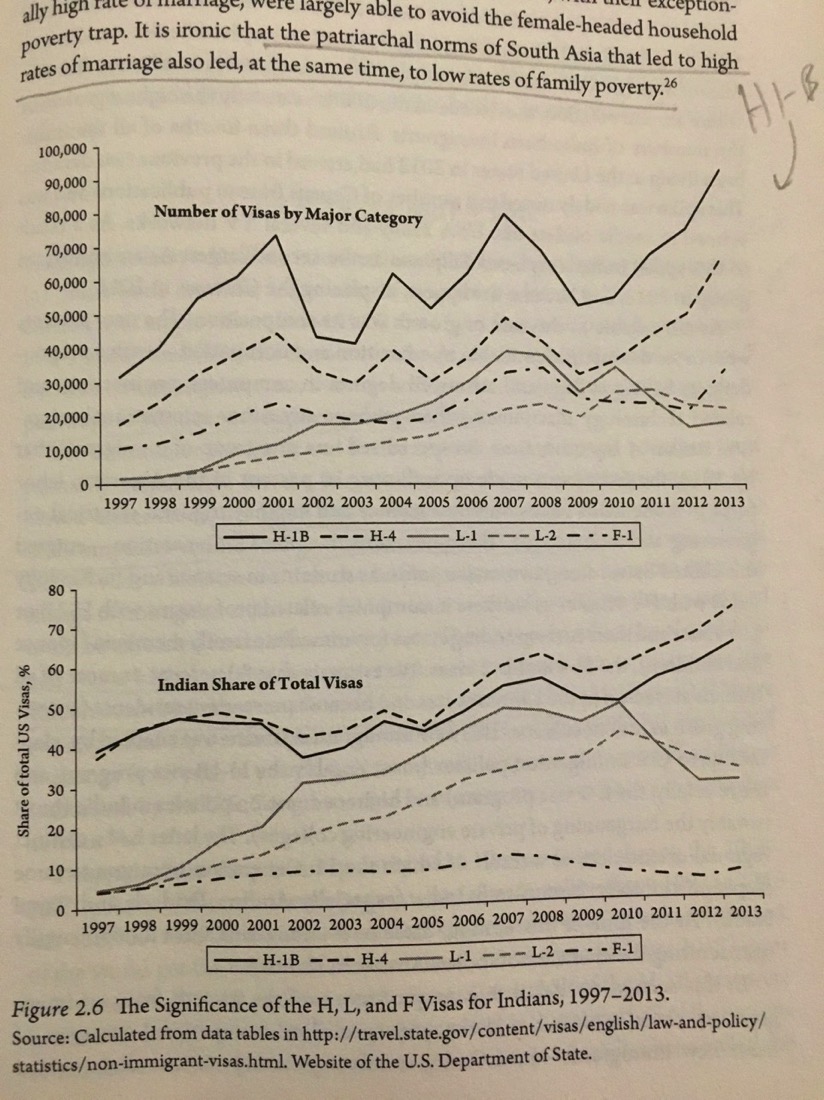

And here’s data on the boom in H–1B visas (a topic on which I’ve reported before) issued to highly skilled workers – and Indians’ huge proportion of those.

Finally, while the book argues that “the success of Indian Americans is at its core a selection story,” the authors do touch on other potential factors. These include:

- “thrift and pooling of savings”

- English language skills

- strong social networks

- “cohesive families”

- an experience with social heterogeneity in India that has made them more “adaptable”

I highly recommend “The Other One Percent” for those interested in immigration and immigration policy, the Indian diaspora, and American society broadly.