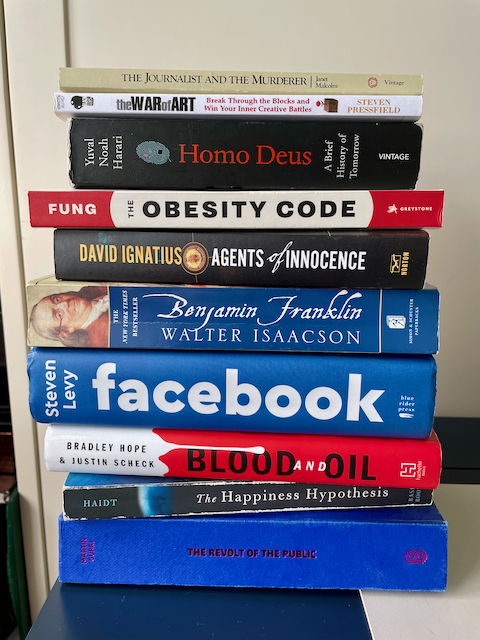

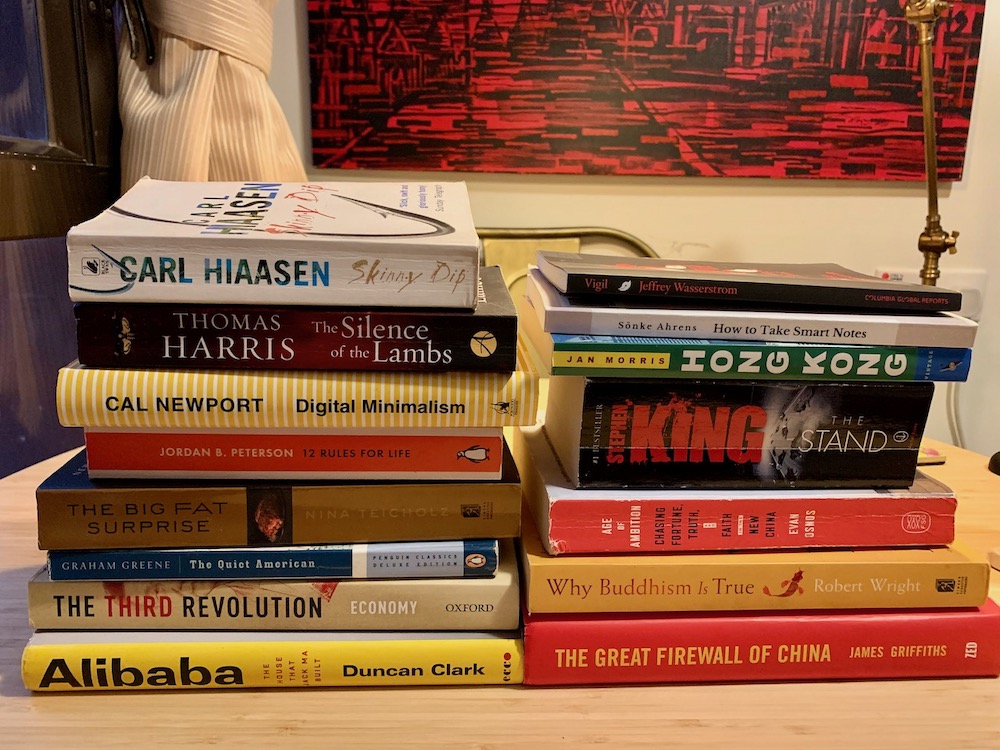

Here's my annual rundown of the standout books I read this year.

Like in previous roundups, I’m not confining myself to books published in the last 12 months.

My nonfiction picks span the global semiconductor industry, equitable parenting, and – thanks to Netflix – the Indian guru Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh.

For fiction, I completed a trilogy by my new favorite spy thriller author and took in a sprawling Jonathan Franzen family saga.

As ever, I prefer physical books over e-books. I like the sensory experience of holding books in my hands. I like gazing at the cover art. I like tracking my progress through the pages and flipping forward and backward. And most of all, I like the ability to mark up the pages for future reference.

My reading wasn't as focused on particular topics as it's been in previous years. But I've tried to keep in mind what the great Charlie Munger once said: “As long as I have a book in my hand, I don’t feel like I’m wasting time.”

Here goes:

Nonfiction

- Chris Miller, Chip War: The Fight for the World's Most Critical Technology – This acclaimed 2022 book provides a timely, accessible introduction to the global semiconductor industry. Miller, a history professor at Tufts University, describes how scientists developed the staggeringly complex technology over the decades.

He also shows why semiconductors are crucial for everything from missiles to smartphones and kitchen appliances. And the book hammers home just how vulnerable global semiconductor supply chains are to geopolitical tensions, and makes clear why Beijing is pouring resources into bolstering China's domestic chip-making capabilities. -

Russell King, Rajneeshpuram: Inside the Cult of Baghwan and Its Failed American Utopia – Like many others, I enjoyed the 2018 Netflix documentary series “Wild, Wild Country.” I found the series fascinating given my roots in Eastern Oregon and our time in India, so I decided to do some reading on the movement.

In this book, out last year, Russell King puts his skill as an attorney to work in reconstructing a timeline of Baghwan's life in India. King documents the growth of Baghwan's ashram in Pune, and then his migration to rural Oregon in the early 1980s, where the documentary picks up.

While the Netflix series is sympathetic to many members of the group interviewed, including the memorable Ma Anand Sheela, Rajneeshpuram includes a fuller account of the group's many alleged crimes and misdeeds in Oregon. They include the poisoning of more than 700 people in a town near the Rajneeshees' ranch that still ranks as the U.S.'s largest biological terror attack, plans to assassinate public officials, the disregard for homeless people brought to the ranch, and the forced isolation of Rajneeshees who contracted HIV.

-

Subhuti Anand Waight, Wild Wild Guru: An insider's account of his life with Bhagwan, the world's most controversial guru – Next up was this 2019 account by a Bhagwan devotee who left a job in journalism in the UK to live in the guru's Pune ashram, then later traveled westward to the U.S.

The book provides a sense of Baghwan's appeal to hippies at the time: You can strive to reach enlightenment, he preached, but rather than sacrifice earthly delights as an ascetic would, you can still indulge in all manner of corporeal pleasures.

Perhaps most instructive for me was to see how a devotee can, after all these years, appear to gloss over the great damage the Rajneeshees inflicted on neighbors and various vulnerable people. The author's message seems to be: We were a religious movement persecuted for being different; sure, there were a few bad apples, but no one knew about their shenanigans; ultimately those uptight Americans just couldn't accept us for being different.

-

George Friedman, The Storm Before the Calm: America's Discord, the Coming Crisis of the 2020s, and the Triumph Beyond. Geopolitical forecaster Friedman in his well-known The Next 100 Years looked at global trends. In this 2020 book he projects what's in store for the U.S.

Friedman says this decade will continue to prove tumultuous because a historical cycle that governs institutional change is converging with a similar socio-economical cycle. He's bullish on the U.S. over the long term, though, because the country is blessed with a favorable geography, a powerful economy, and an inherent dynamism. We'll weather the storm, he argues.

-

Eve Rodsky, Fair Play: A Game-Changing Solution for When You Have Too Much to Do (and More Life to Live). My wife, who is brilliant and well-read, suggested this 2019 book. I'm glad she did.

Rodsky, trained as a lawyer, provides a template for couples that encourages men to own their share of work that goes into running a household and raising kids. That way, “shefault” parents — women — can do less of the cognitive, invisible labor that make homes function.

Fiction

-

Jonathan Franzen, Crossroads: a Novel I didn't expect to find a nearly 600-page-long family saga set in 1970s Illinois and focusing on a minister and his family to be so absorbing, but I did.

Perhaps that's a testament to Franzen's storytelling skills, or simply my tastes, as I've read nearly everything he's written. In this 2021 work, I loved the characters (particularly the memorable Marion Hildebrandt), I loved the dialogue, I loved the vivid scenes. Apparently the first in a trilogy. I'll be reading the titles that follow.

-

Jason Matthews, The Palace of Treason and The Kremlin's Candidate. Thanks to my friend Stuart H. for suggesting, since I love spy fiction, that I check out 2013's Red Sparrow trilogy.

The first in the series, called Red Sparrow: a Novel, introduces us to Russian spy Dominika Egorova and her handler, Nathanial Nash. This year I enjoyed the final two books, which came out in 2015 and 2018.

Matthews spent more than three decades as a CIA officer, mostly stationed abroad and involved in clandestine work, before trying his hand at fiction. The books contain detailed depictions of modern spy-craft, are well-paced, and are imbued with Matthews's take on modern-day Russia. Among the characters, for example, is one Vladimir Putin.

Matthews also no doubt drew upon his years of experience to portray idealistic but imperfect CIA staff who fight for America's interests. Sadly, he died a few years ago at the age of 69, leaving just the three books behind.

-

Ernest Cline, Ready Player One Some works of fiction are so frequently discussed that you have to read them to know what everyone's talking about. This 2011 book is one.

Set in a dystopian 2045, it is popular for its focus on 1980s pop culture, such as video games and music, which are of course ancient history for the book's characters. Viewed today, with Mark Zuckerberg and other believers touting the metaverse it's interesting to see how Cline viewed the possibility of future virtual realms taking shape.

My previous annual best books lists: 2022, 2021, 2020, 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016.

Photo by CEphoto, Uwe Aranas. Antwerp, Belgium: Interior of Museum Plantin-Moretus, via Wikimedia Commons