I was traveling when Lee Kuan Yew, Singapore’s founding father, died Monday, and haven’t had a chance to blog about his passing until now. (Pictured above: a recent sampling of Singaporean newspapers’ front pages.)

Here are some links I suggest checking out.

The WSJ obituary:

Lee Kuan Yew, who dominated Singapore politics for more than half a century and transformed the former British outpost into a global trade and finance powerhouse, setting a template for emerging markets around the world, died Monday. He was 91 years old.

And here’s the NYT obit, as well.

My colleague Shibani Mahtani, a Singaporean who lives abroad, at WSJ Expat on the significance of Lee’s death for her countrymen:

Singaporeans are a lucky breed—we do not have memories of coups or mass protests or riots or severe terrorist attacks in recent years, unlike most of our neighbors. In many ways, the passing of Mr. Lee is the deepest loss that the country has felt, together, in a generation. It is also a reminder of the fragility of the nation, and how its history could have gone in a completely different direction if not for Mr. Lee’s vision.

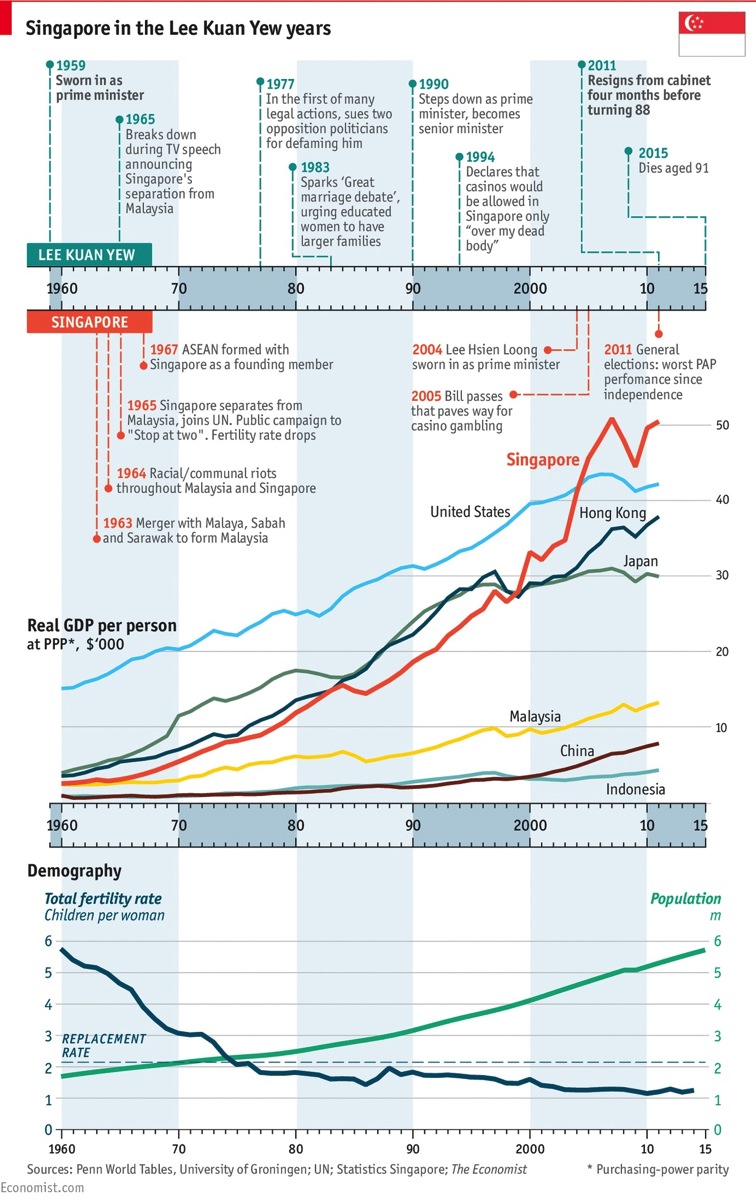

Elsewhere, The Economist charts the remarkable rise in Singapore’s per capita GDP — and low fertility rates:

What comes next for Singapore? Here’s our story:

Mr. Lee, who died at 91 on Monday, has been widely credited for turning what had been a malaria-ridden British trading post into a gleaming economic success story. Singaporeans now enjoy a standard of living comparable with Japan and advanced European and North American economies, albeit without a pluralistic political system, a free press or strong dissenting voices.

But what comes next? In many ways, Singaporeans have been quietly preparing for a future without the steadying influence of the republic’s founding father.

The past four years were the first for independent Singapore without Mr. Lee in government. He stepped down from his advisory role of “minister mentor” in the cabinet in 2011, just a week after the ruling People’s Action Party recorded its worst electoral showing in five decades—a result government officials and political observers have attributed to festering socioeconomic tensions in recent years.

And here’s our look at Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong — Lee Kuan Yew’s son:

He has been prime minister of Singapore since 2004, but Lee Hsien Loong was inevitably overshadowed by his celebrated father, Lee Kuan Yew, who died this week.

The younger Mr. Lee faces the task of carrying forward his father’s legacy in his own style at a time when Singapore confronts social and economic challenges that have seen support for the governing People’s Action Party erode more than at any time since it came to power in 1959.

Politically, Ernest Bower at the Center for Strategic and International Studies says:

Some of PAP’s leaders may pine for the old days, but hopefully they won’t pursue the path of their counterparts in Malaysia, where the ruling United Malays National Organization party seems to be trying to turn the clock back, betting on an ultra conservative approach.

It is more likely that over time, PAP’s well-educated and globally focused leaders will find there is new room to breathe and innovate in the new political space of the post-Lee Kuan Yew era.

Meanwhile, we also ran a long, very interesting Orville Schell essay about the “Singapore model” and the future Asia. It concludes:

Lee Kuan Yew not only made Singaporeans proud; he also made Chinese and other Asians proud. He was a master builder, a sophisticated Asian nationalist dedicated not only to the success of his own small nation but to bequeathing the world a new model of governance. Instead of trying to impose Western political models on Asian realities, he sought to make autocracy respectable by leavening it with meritocracy, the rule of law and a strict intolerance for corruption to make it deliver growth.

Though his country was minuscule, Lee was a larger-than-life figure with a grandness of vision. He saw “Asian values” as a source of legitimacy for the idea that authoritarian leadership, constrained by certain Western legal and administrative checks, offered an effective “Asian” alternative to the messiness of liberal democracy. Because his thinking proved so agreeable to the Chinese Communist Party, he became the darling of Beijing. And because China has now become the political keystone of the modern Asian arch, Beijing’s imprimatur helped him and his ideas to gain a pan-Asian stature that Singapore alone could not have provided.

As countries such as Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, Sri Lanka and even China continue to search for new models of development and governance that do not bear the stigma of their former Western colonizers, Lee Kuan Yew’s example is a tempting option. Even though he is now gone, the Venice-like republic he founded will continue to be extolled as a hopeful experiment, and the man himself, the progenitor of what has come to be known as the “Singapore model,” will doubtless remain an influential political evangelist.

Read the whole thing.

And finally:

Embedded above and on YouTube here: Lee Kuan Yew on “Meet the Press” in 1967. He discusses the Vietnam war and Southeast Asia. An interesting slice of history.